Fewer units allocated for community members

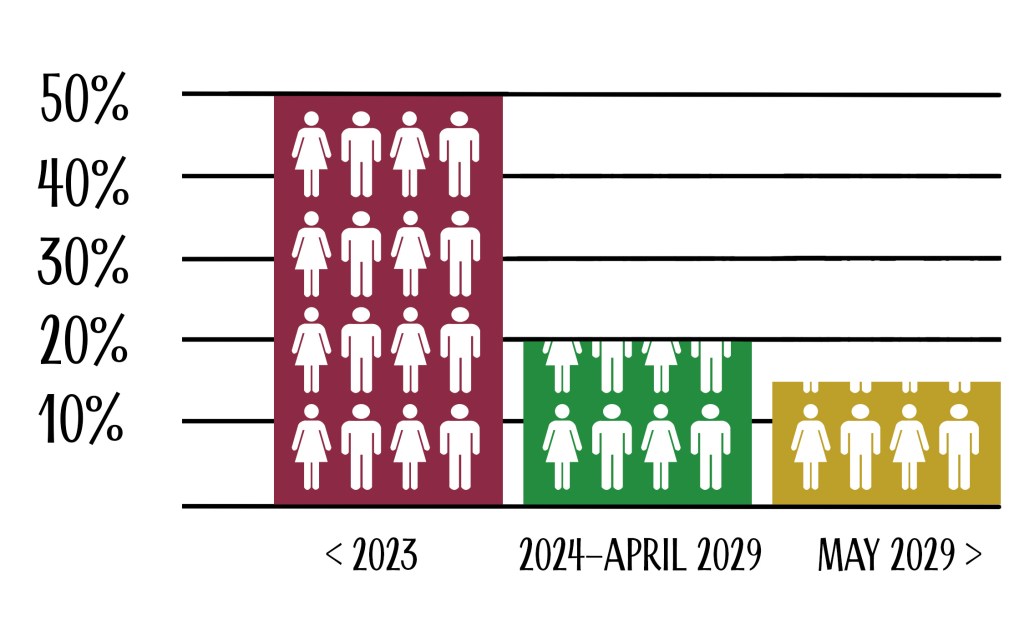

New York City’s affordable housing lottery system used to allocate fifty percent of its units for residents already living in the development’s community, otherwise known as the community preference policy. Now, NYC holds fewer spots for community preference.

On January 22, Chief District Judge Laura Taylor Swain approved a settlement agreement between NYC and the plaintiffs, three African American women, who filed a lawsuit in 2015. The women applied multiple times for housing lottery apartments in Manhattan neighborhoods and were rejected. They argued to eliminate the community preference policy because it perpetuates segregation and is a violation of the Fair Housing Act and NYC Human Rights Law. The City agreed to pay the two plaintiffs (one quit the case in 2018) $100,000 each and over $6 M in attorney and other fees.

Community preference will now be limited to twenty percent for all new NYC Housing Development Corporation (HDC) apartments. The limit will change again in May of 2029 to fifteen percent. Those who have other special considerations on their applications, such as disability set-aside units or homelessness, and they have applied for an apartment with geographic preference will still count towards the community preference cap.

“Most New Yorkers agree that the City needs more—and more affordable—housing. But given the small number of genuinely affordable units being built, there are legitimate questions about whom we want the units to serve,” said Adam Meyers, the director of litigation at Communities Resist. “Limiting the community preference will help to expand access to high opportunity neighborhoods more broadly, but it will also make it harder for the residents of gentrifying neighborhoods—those impacted directly by new construction and rising rents that can accompany it—to remain in the communities they’ve long called home.”

Former Mayor Ed Koch initiated the community preference policy in 1988 at 30 percent. The City argued it would help low-income applicants, assist with integration, and prevent displacement during gentrification. Often, community preference promoted affordable housing by gaining support from NYC Council Members due to its benefits for their constituents.

The debate over community preference has been ongoing for years. What started as a 30 percent preference rose to 50 percent during Mayor Bloomberg’s candidacy. During this time, a settlement case between Bloomberg and the Broadway Triangle Coalition gave community preference to more than one neighborhood on the Broadway Triangle development bordering Williamsburg, Bushwick, and Bed-Stuy.

“The community preference option stemmed from the voices of displaced families and service providers who struggled to secure housing for vulnerable neighbors. And much of that advocacy originating right here in North Brooklyn, where residents witnessed inaccessible residential developments, and the devastating displacements out of the only communities they knew,” said NYC Council Member Jennifer Gutiérrez. “While I understand the argument and issue of segregation, in communities like ours, with evolving dynamics in housing accessibility, I am disheartened that a solution to one of the number one issues will become that much harder to achieve.”

Other cities also have housing preference policies. In Oregon, Portland’s N/NE Preference Policy “aims to address the harmful impacts of urban renewal by giving preference to housing applicants with generational ties to North/Northeast Portland.” San Francisco has various qualifiers that give applicants preference, including displacement.

With the new settlement, applicants living outside of a desired community have a better chance of getting an apartment there through the housing lottery. Only time will tell how this shift will affect NYC’s affordable housing landscape.